In Memoriam: Steve York

Steve York, filmmaker, teacher, father, partner, died August 19, 2021 from vascular disease. He was 78 years old.

Howard York hand-in-hand with Steve and Carolyn, late 1940s

His roots were in St. Louis where he grew up with his parents, Howard and Bobbie, and sister, Carolyn. Howard had worked in the Civilian Conservation Corps during the Depression and raised his kids on tales of his toil and sweat constructing flood barriers, painting Danger Dynamite signs, and manning fire towers out west. His dad instilled two things that would carry Steve through life: the impulse to tell stories and the belief that he could build anything with his own two hands.

Steve York, ham operator in his basement, c. late 1950s

Early Life in St. Louis

Steve could build a solution to meet almost any need. As a youngster he built prize-winning science fair projects. As a young man, he designed and built sets for theater. As a filmmaker, he would fashion whatever platform, storage or shelving was essential for his work. His greatest pleasure, though, was in building things for his family, bunk and sleigh beds for his children, flower presses for his wife, sheds, arbors and trellises for the garden, and all manner of tables and benches, from simple to refined.

Working with his hands was a creative release, a great counterbalance to his passion for chronicling the world around him. The drive to communicate started early. In high school, he edited the newspaper, acted in numerous plays, and competed as a public speaker. He made the leap from basement ham radio operator to paid disc jockey and engineer at a classical musical station when he was just sixteen.

Steve York at Washington University, May 1967

At Washington University, Steve explored different ways to tell stories. He acted and worked tech in numerous plays, edited the student newspaper, co-authored a satirical coloring book with classmate and future editorial cartoonist, Mike Peters, and started making films.

By his early 20s, Steve’s professional experience included producing and directing live TV in Denver, designing sets and lighting for St. Louis’s Gateway Theatre, and stage managing the Opera Theatre of St. Louis. He loved working in theater but it gradually became clear he could make a steadier living in film and television.

Impersonating an Army combat photographer, c. 1968, inset, Pvt Steve York

Photographer in Europe

In 1967, Steve was working in film production during the day and teaching filmmaking at night when the Army messed with his plans. His skill with the camera spared him. Thanks to film business connections, Steve was assigned first as a motion photographer at the Army Pictorial Center in Astoria, Queens, then as a still photographer to the 3rd infantry, 123rd Signal Corps battalion based in Wurzburg, Germany.

As someone who bristled at being told what to do, Steve hated the Army but he was determined to see, learn, and experience as much as he could. His official duties had him shooting everything from sports events and medal ceremonies to aerial scenes and autopsies, but it wasn’t enough. He talked his way into reassignment as a writer-reporter-photographer for the division newspaper. He also took on graphic design and layout for publications.

In his free time, Steve honed his craft. He wandered the streets with his still camera, capturing faces, street scenes, and old buildings for his portfolio. To pick up cash, he shot portraits and worked crew for a documentary being filmed near the base. He used the extra money to buy tickets to as many concerts, plays, and operas as he could, and to finance trips to Paris, London, and beyond. Somehow he also found time to direct a play for a local theater group.

Prague street protests, August 1969, photo by Steve York

The years 1968 and 1969 were filled with political turmoil. Steve was reading multiple newspapers a day, in English, French and German, to keep up on the news, a daily practice he would continue for life. As a soldier, he had to observe from the sidelines but as soon as he got his honorable discharge in 1969, he packed up his camera gear and took the train to Prague to photograph life under Soviet control. He befriended a group of Czech students and documented their actions, from their kitchen meetings to their confrontations with the police and subsequent escapes down tear gas filled alleys. Steve smuggled some 50 rolls of undeveloped film back into Germany and sold his photos to the Associated Press.

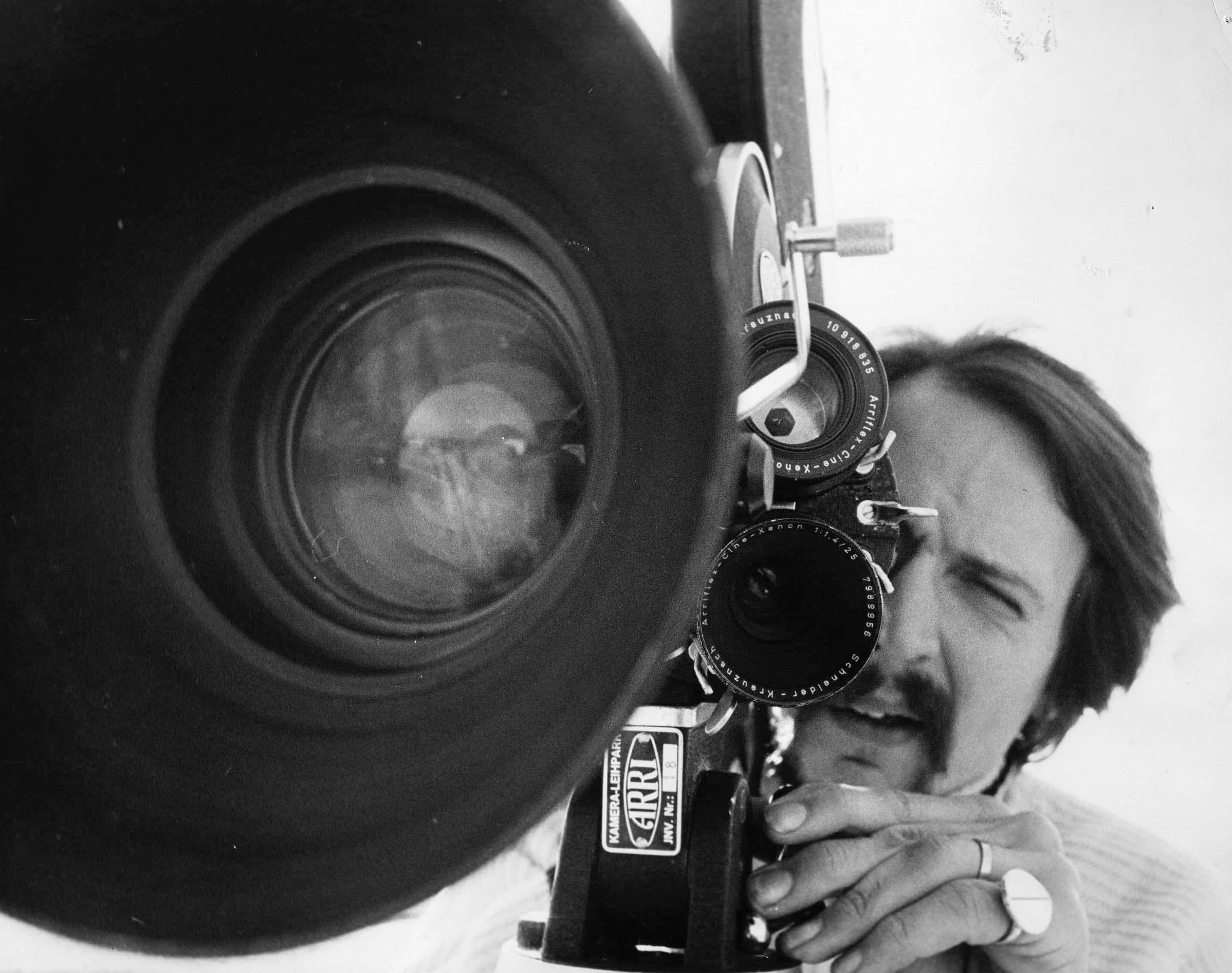

Steve York, late 1970s

Filmmaker Around The World

In June 1972, a day after the Watergate break-in, Steve returned to the States for good. He started as a negative cutter at a Washington, DC film lab but moved up and out quickly. By the end of the decade, he was editing, producing, and directing films for Bill Moyers and Charles Guggenheim.

Over the course of his 40-year career, Steve would shoot, edit, produce, write, and direct countless productions, on topics ranging from war and politics to justice and art, stories and events that changed the world. His style was understated; he trusted his viewers’ intelligence to find meaning in the images and words he wove together for the screen.

Steve York on location at the Smithsonian with Foster Wiley, c. 1980

Steve’s favorite work was “Vietnam Memorial,” a one-hour film he made with Foster Wiley about the days surrounding the dedication of the national Vietnam Memorial in 1982. Constructed without narration, the viewpoint is that of the veterans as they assemble to reminisce and mourn what they lost and found, and how they were treated when they returned. “Vietnam Memorial” was rebroadcast on national PBS for years as part of its Veteran’s Day celebrations. Every time Steve watched it, he would cry.

Steve York on location in Japan, with cinematographer Ivan Strasburg, 1985

He carried his passport with him at all times, taking crews all over North and South America, Europe, Africa and Asia. The trio of films he made on successful civil resistance movements may have had the greatest global impact. They educated millions on how regular people had used nonviolent weapons like strikes and marches to overcome authoritarian regimes. “A Force More Powerful,” “Bringing Down a Dictator” and “Orange Revolution” have been translated into some twenty languages, and broadcast, smuggled, bootlegged, analyzed, and screened in China, Russia, Belarus, Iran, Cuba, Venezuela, and many other countries where activists are leading struggles for democracy. The films became a tool for those mounting resistance movements. Governments banned them, alongside their director, Steve York.

Steve York on location at Pearl Harbor with David Brinkley, 1991

For all his accolades and awards, the only approval Steve was seeking was his own and that of his filmmaking partners. Celebrity and wealth neither interested nor impressed him. He prized hard work, dedication, and excellence, in himself and in others, although he rarely praised it.

Friend, Father, Partner

While he did not suffer fools gladly, Steve was by nature kind and patient. He led with respect. In his work and personal life, he didn’t excavate someone’s weak spots; he would simply put on his teaching hat and explain clearly—how to work a new piece of equipment, why the effects of colonization are still so devastating, when you should add the fresh herbs into the pan -- until the listener understood.

Steve York with Palestinian doctor Jihad Mashal, 2001

As an army buddy pointed out, “Steve knew something about everything, and everything about photography.” He was a mentor to many, encouraging talent when he saw it, always willing to comment on a rough cut, share contacts, give advice, tell stories, teach.

On location, in the office, and over the delicious dinners he cooked for family and friends, Steve shared his knowledge and experience. “He seemed to bring the whole world to every discussion,” one friend wrote upon learning of his death, “but he was always keen on listening to and learning from others.”

This habit of listening and learning defined Steve’s career as a filmmaker and as a human being. He kept the door open for discovery, his and yours.

We will miss him every day.

Steve is survived by his wife and partner of more than 30 years, Miriam Zimmerman, their daughter, Rebecca, and two daughters from his first marriage, Vanessa and Joanna.

Steve York on location on the Nile, Cairo, 2012